The Machine, the Ghost, and the Limits of Understanding

I'll talk some about Isaac Newton and his contributions to a study of mind. He's not known for that, but I think a case can be made that he did make substantial, indirect but nevertheless substantial contributions. I'd like to explain why.

There is a familiar view that the early Scientific Revolution, beginning and through the 17th century, provided humans with limitless explanatory power, and that conclusion is established more firmly by Darwin's discoveries, the theory of evolution. I'm having in mind, specifically, a recent publication, an exposition of this view by two distinguished physicists and philosophers, David Albert and David Deutsch. But it's commonly held, with many variants.

There's a corollary: the corollary is ridicule of what's called by many philosophers 'Mysterionism.' That's the absurd notion that there are mysteries of nature that human intelligence will never be able to grasp. It's of some interest to notice that this belief is radically different from the conclusions of the great figures who actually carried out the early Scientific Revolution. Also, interesting to notice how inconsistent it is with what the theory of evolution implies and has always been understood to imply since its origins.

And I'd like to say a few words about those two topics in turn.

Start with David Hume's 'The History of England.' It's, of course, a chapter on the Scientific Revolution and, in particular, on the crucial role of Isaac Newton, who he describes as 'the greatest and rarest genius that ever arose for the ornament and instruction of the species.' Hume concluded that Newton's greatest achievement was that while he seemed to draw the veil from some of the mysteries of nature, he showed at the same time the imperfections of the mechanical philosophy and thereby restored nature's ultimate secrets to that obscurity in which they ever did and ever will remain.

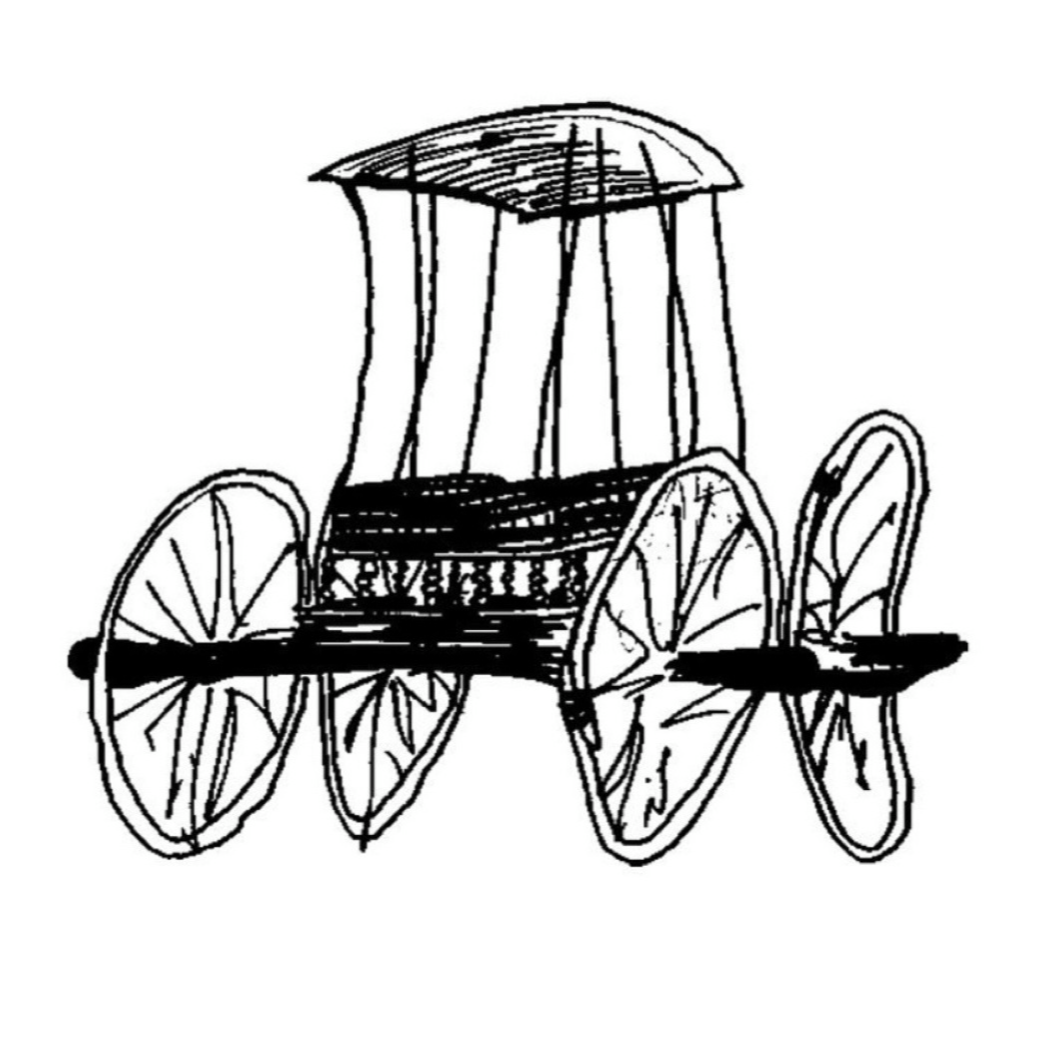

The mechanical philosophy, of course, was the guiding doctrine of the Scientific Revolution. It held that the world is a machine, a grander version of the kind of automata that stimulated the imagination of thinkers of the time, much in the way programmed computers do today.

They were thinking of the remarkable clocks, the artifacts constructed by skilled artisans, most famous was Jacques de Vaucanson, some devices that imitated the digestion, animal behavior, or the machines that you could find in the Royal Gardens as you walk through, they pronounced words, and when they were triggered, and many other such devices. The mechanical philosophy wanted to dispense with occult notions, do away with scholastic notions of forms flitting through the air, sympathies and antipathies, such are occult ideas. And it wanted to be hard-headed, to keep to what's grounded in common sense understanding, and it, in fact, provided the criterion for intelligibility from Galileo through Newton and, indeed, well beyond.

Well, it's well known also that Descartes had claimed to have explained the phenomena of the material world in such mechanical terms, while also demonstrating that they're not all-encompassing, don't reach into the domain of mind. In his view, he therefore postulated a new principle to account for what was beyond the reach of the mechanical philosophy. And while this too was sometimes ridiculed, it's, in fact, in full accord with normal scientific, not scientific method. He was working within the framework of substance philosophy, so the new principle was a second substance, his 'res cogitans.' And then there's a scientific problem that he and others faced: determining its character and determining how it interacts with the mechanical world. That's the mind-body problem, cast within the Scientific Revolution. That it's a scientific problem, well, it was for a time.

The mechanical philosophy was shattered by Newton, as Hume did, and with it went the notion of understanding of the world that the Scientific Revolution sought to attain. And the mind-body problem also disappeared, and I don't believe has been resurrected, though there's still a lot of talk about it. Those conclusions were pretty well understood in the centuries that followed, they've often been forgotten today.

John Locke had already reached conclusions rather similar to Hume's. He was exploring the nature of our ideas, and he recognized, I'll quote him, 'that body, as far as we can conceive, is able only to strike and affect body, and motion, according to the utmost reach of our ideas, is able to produce nothing but motion.' These are the basic tenets, of course, of the mechanical philosophy. They yield the conclusion that there can be no interaction without contact, which is our common sense intuition. And modern research in cognitive science has given a lot of, have given pretty much, pretty solid grounds for Locke's reflections on the nature of our ideas. It's revealed that our common-sense understanding of the nature of bodies and their interactions as, no nowadays, we would say, in large part, genetically determined. It's a lot, it's very much as Locke described.

Very young infants can recognize a principle of causality through contact, not in any other way. If they recognize causality, they seek a hidden contact somewhere. And those, in fact, appear to be the limits of our ideas, of our common sense. The occult ideas of the Scholastic's or of Newton, Newtonian attraction, it goes beyond our understanding, and is unintelligible, at least by the criteria of the Scientific Revolution.

Very much like Hume, Locke concluded, therefore, that we may, we remain in incurable ignorance of what we desire to know about matter and its effects. 'No science of bodies is within our reach,' and he went on to say, 'we could only appeal to the arbitrary determination of that all-wise agent who has made them to be and operate as they do, in a manner wholly above our weak understanding to conceive.'

Actually, Galileo had reached much the same conclusions at the end of his life. He was frustrated by the failure of the mechanical philosophy, its ideal, its failure to account for cohesion, attraction, other phenomena, and he was forced to reject, quoting him, 'the vain presumption of understanding everything.' Or, to conclude even worse, 'that there is not a single effect in nature such that the most ingenious theorist can arrive at a complete understanding of it.'

Actually, Descartes, though more optimistic, had also recognized the limits of our cognitive reach. Occasionally, he's not entirely consistent about this, but Rule Eight of his 'Regulae' reads, 'If in the series of subjects to be examined we come to a subject of which our intellect cannot gain a good enough intuition, we must stop there, and we must not examine the other matters that follow, but must remain from refraining from futile toil.' Specifically, that Descartes speculated that the workings of 'res cogitans,' the second substance, may be beyond human understanding. So, he thought, quoting him again, 'we may not have intelligence enough to understand the workings of mind,' in particular the normal use of language, one of his main concepts.

He recognized that the normal use of language, as what has come to be called a creative aspect, it's every human being, but no beast, no machine, has this capacity to use language in ways that are appropriate to situations, but not caused by them. That's a crucial difference. And to formulate and express thoughts that may be entirely new, and to do so without bound, may be incited or inclined to speak in certain ways by internal and external circumstances, but not compelled to do so. It's the way his laws, but the matter which was a mystery to Descartes, and remains a mystery to us, though quite clearly as a fact.

Well, Descartes nevertheless continued that even if the explanation of normal use of language, and other forms of free and coherent choice of action, even if that lies beyond our cognitive grasp, as it apparently does, that's no reason, he said, to question the authenticity of our experience. Quite generally, he said, 'The free will, which is at the core of this, is the noblest thing we have, and there is nothing we comprehend more evidently and more perfectly.' So, it would therefore be absurd to doubt something that we comprehend intimately and experience within ourselves, namely that the free actions of men are undetermined, merely because it conflicts with something else which we know must be, by its nature, incomprehensible to us.

That much, like Locke, he had in mind divine preordination. One of the leading Galileo scholars, Peter Machamer, observes that by adopting the mechanical philosophy, and thus initiating the modern Scientific Revolution, Galileo had forged a new model of intelligibility for human understanding, with new criteria for coherent explanation of natural phenomena. So, for Galileo, real understanding requires a mechanical model, that is, a device that an artisan could construct, at least in principle, hence intelligible to us.

So, Galileo rejected traditional theories of tides because, as he said, we cannot duplicate them by means of appropriate artificial devices. And his great successors adhered to these high standards of intelligibility and explanation. So, it's therefore quite understandable why Newton's discoveries were so stridently resisted by the greatest scientists of the day. Christiaan Huygens described Newton's concept of attraction as an absurdity. Leibniz charged that he was reintroducing occult ideas similar to the sympathies and antipathies of the much-ridiculed Scholastic science and was offering no physical explanation for phenomena of the material world.

And it's important to notice that Newton agreed, very largely agreed. He wrote that the notion of action at a distance is inconceivable. It's 'so great an absurdity that I believe no man who has in philosophical matters a competent faculty of thinking can ever fall into it.' As philosophical means what we call scientific. By invoking that principle, he said, 'we concede that we do not understand the phenomena of the material world.'

So, Newton scholarship recognizes that. I. Bernard Cohen, for example, or pick someone else, points out that by the word 'understand,' Newton still meant what his critics meant: understand in mechanical terms of contact action. Newton did have a famous phrase, which you all know: 'Hypotheses non fingo'—I frame no hypotheses. And it's in this context that it appears. He had been unable to discover the physical cause of gravity, so he left the question open. He said, 'To us, it is enough that gravity does really exist, and act according to the laws which we have explained, and abundantly serves to account for all the motions of the celestial bodies, and of our sea, the tides.'

But while agreeing, as he did, that his proposals were so absurd that no serious scientist could take him seriously, he defended himself from the charge that he was reverting to the mysticism of the Aristotelians. What he argued was that his principles were not occult, only their causes were occult. So, in his words, 'To derive two general principles inductively from phenomena, and afterwards to tell us how the properties and actions of all corporeal things follow from these manifest principles, would be a very great step in philosophy, though the causes of the principles were not yet discovered.

And by the phrase 'not yet discovered,' Newton meant, the word 'yet' is crucial here, he was expressing his hope that the causes would someday be discovered in physical terms, meaning mechanical terms. That was a hope that lasted right through the 19th century, but it was finally dashed by 20th-century science. So, that hope is gone. The model of intelligibility that reigned from Galileo through Newton, and well beyond, has a corollary: when mechanism fails, understanding fails.

So, Newton's 'absurdities' were finally, over time, just incorporated into common-sense Natural Science; we study them in school today. But that's quite different from common-sense understanding. So to put it differently, one long-term consequence of the Newtonian revolution was to lower the standards of intelligibility for natural science. There's the hope to understand the world, which did animate the modern scientific revolution, that was finally abandoned. It was replaced by a very different and far less demanding goal, namely to develop intelligible theories of the world.

As such, further 'absurdities,' as say curved space-time or quantum indeterminacy, were absorbed into the natural sciences. The very idea of an 'intelligibility' is dismissed as absurd, for example, by Bertrand Russell, who knew the sciences very well. By the late 1920s, he repeatedly placed the word 'intelligible' in quotes, to highlight the absurdity of the quest, and he dismisses the qualms of the founders—the great founders of the Scientific Revolution, Newton and others—dismisses them as little more than a prejudice. Although, a more sympathetic and, I think, accurate description would be that they simply had higher standards of intelligibility.

And if you look at the work of leading physicists, they more or less say the same thing. So, a couple of years after Russell wrote, Paul Dirac wrote a well-known introduction to quantum mechanics in which he says that 'physical science no longer seeks to provide pictures of how the world works, that is a model functioning on essentially classical lines, but only seeks to provide a way of looking at the fundamental laws which makes their self-consistency obvious.' So we understand the theories we've given up trying to understand the world.

He was referring, of course, to the inconceivable conclusions of quantum physics. But if modern thinkers hadn't forgotten the past, he could just as well have been referring to the classical Newtonian models, which were undermined by Newton, undermining the hope of rendering natural phenomena intelligible. That was the primary goal, the animating spirit of the early Scientific Revolution.

There's a classic nineteenth-century history of materialism by Friedrich Lange, translated into English with an introduction by Russell. Lange observes that we have so accustomed ourselves to the abstract notion of forces, or rather to a notion hovering in a mystic obscurity between abstraction and concrete comprehension, that we no longer find any difficulty in making one particle of matter act upon another without immediate contact through void space, without a material link. From such ideas, the great mathematicians and physicists of the 17th century were far removed. They were genuine materialists; they insisted that contact mediates contact as a condition of influence. This transition, he says, was one of the most important turning points in the whole history of materialism. It deprived the notion of much significance, if any at all. And with materialism goes the notion of physical, of body; other counterparts, they have no longer any significance.

He adds that what Newton held to be such a great absurdity that no philosophic thinker could light upon it, is prized by posterity as Newton's great discovery of the harmony of the universe. Those conclusions are quite commonplace in the history of science. So, 50 years ago, Alexander Koyré, another great historian of science and scientist, observed that, despite his unwillingness to accept the conclusion, Newton had demonstrated that a purely materialistic pattern of nature is utterly impossible, and a purely materialistic or mechanistic physics as well. His mathematical physics required the admission into the body of science of incomprehensible and inexplicable facts, imposed on us by empiricism, that is, by what we conclude from observations.

Despite this recognition, the debates did not end. So, about a century ago, Boltzmann's molecular theory of gases or Kekulé's structural chemistry, in fact, even Bohr's atom, which you learn in school, these were only given an instrumental interpretation. A modern history of chemistry, a standard history, points out that they were regarded as calculating devices, but with no physical reality.

Newton's belief that the causes of his principles were 'not yet discovered,' implying that they would be, was echoed, for example, by Bertrand Russell in 1927. He wrote that chemical laws cannot at present be reduced to physical laws, much like Newton, he hoped it would happen, an expectation that it would. But that expectation also proved to be vain, as vain as Newton's. Shortly after Russell wrote this, it was shown that chemical laws will never be reduced to physical laws, because the conception of physical laws was erroneous. This was finally done in Linus Pauling's quantum theoretic account of the chemical bond.

But very much as in Newton's day, the perceived explanatory gap, as it's now called by philosophers, was never filled. Today, interestingly, just a few years ago, we read of the thesis of the 'new biology,' that things mental, indeed minds, are emergent properties of brains. Though these emergences are produced by principles that we do not yet understand, that's neuroscientist Vernon Mountcastle, formulating the guiding theme of a collection of essays reviewing the results of what was called the 'decade of the brain,' the last decade of the 20th century. His phrase, 'we do not yet understand,' might very well suffer the same fate as Russell's similar comment about chemistry seventy years earlier, or for that matter, Newton's much earlier one.

In fact, in many ways, today's theory of mind is recapitulating errors that were exposed in the 1930s with regard to chemistry, and centuries before that with regard to core physics, though in that case, leaving us with a mystery that may be a permanent one for humans, as Hume actually asserted. Throughout all this, and today as well, we can optimistically look forward to unification of some kind, but not necessarily reduction, which is something quite different. Talk about reductionism is highly misleading. It's been abandoned over and over again in the history of science, seeking unification, a much weaker goal, sometimes, in the case of the classic case of Newton, and what he left veiled in mystery, that's may involve a significant lowering of expectations and standards.

Well, let me go back to the beginning, the exuberant thesis that the early Scientific Revolution provided humans with limitless explanatory power. If we look over the history, I think quite a different conclusion is in order. The founders of the Scientific Revolution were compelled by their discoveries to recognize that human explanatory power is not only not limitless but does not even reach to the most elementary phenomena of the natural world. That's masked by lowering the criteria of intelligibility, of understanding.

Well, according to what we've discussed, if we accept that much, as I think we should, a less ambitious question arises. The goals of science, having been lowered to finding intelligible theories, we can sensibly ask: Can we maintain that humanly accessible theories are limitless in their explanatory scope? It's a much weaker goal. Furthermore, does the theory of evolution establish the limitless reach of human cognitive capacities? Actually, if you think about it, the opposite conclusion seems much more reasonable.

The theory of evolution, of course, places humans firmly within the natural world. It regards humans as biological organisms, very much like others, and for every such organism, its capacities have scope and limits — they go together. That includes the cognitive domain. So, rats, for example, can't solve, say, a prime number maze, because they lack the appropriate concepts. It's not a lack of memory or anything like that; they just don't have the concepts. So, for rats, we can make a useful distinction between problems and mysteries. Problems are tasks that lie within their cognitive reach, in principle. Mysteries are ones that don't. Mysteries for rats then may not be mysteries for us.

If humans are not angels, if we're part of the organic world, then human cognitive capacity is also going to have scope and limits. So, accordingly, the distinction between problems and mysteries holds for humans, and it's a task for science to delimit it. Maybe we can, maybe we can't, but at least it's a formulable task. And it's not inconsistent to think that we might be able to discover the limits of our cognitive capacities. Therefore, those who accept modern biology should all be 'mysterians,' instead of ridiculing it, because mysterianism follows directly from the theory of evolution, everything we scientifically believe about humans.

So, the common ridicule of this concept, right through philosophy of mind, what it amounts to, is the claim that somehow humans are angels, exempt from biological constraints. And, in fact, far from bewailing the existence of mysteries for humans, we should be extremely grateful for it. Because if there are no limits to what we might call, say, the science-forming capacity, it would also have no scope, just as if the genetic endowment imposed no constraints on growth, it would mean that we could be, at most, some shapeless amoeboid creature, reflecting accidents of an unanalyzed environment. The conditions that prevent a human embryo from becoming, say, an insect or a chicken, those very same conditions play a critical role in determining that the embryo can become a human. You can't have one without the other, and the same holds in the cognitive domain.

Actually, classical aesthetic theory recognized that. They recognized that there's a relation between scope and limits. Without any rules, there can be no genuine creative activity, and that's even the case when creative work challenges and revises prevailing rules. So, far from establishing the limitless scope of human cognitive capacities, modern evolutionary theory, and in fact all standard science, undermines that hope. Now, that was actually appreciated right away when the power of the theory of evolution came to be recognized.

One enlightening case is Charles Sanders Peirce and his inquiry into what he called 'abduction,' which is rather different from the way the term is used today. Peirce was struck particularly by a striking fact that in the history of science, major discoveries are often made independently and almost simultaneously, which suggests that some principle is directing inquiring minds towards that goal, under the existing circumstances of understanding. Something similar is true for early childhood learning. So, if you put aside pathology or extreme deprivation, children are essentially uniform in this capacity, and they uniformly make quite astounding discoveries about the world, going well beyond what any kind of data analysis could have yielded. In the case of language, it's now known that that starts even before birth. So, a child is born with some conception of what counts as a language, and can even recognize its mother's language as distinct from another language, both spoken by a bilingual woman who's never heard before. These interesting distinctions, determining how it works, can be done at birth, and in fact, even the first step of language acquisition, which is generally taken for granted, it's quite a remarkable achievement. An infant has to select from the environment, from what William James called 'the blooming, buzzing confusion,' the infant has to somehow select the data that are language-related. It's a task that's a total mystery for any other organism; they have absolutely no way of doing it. But it's a reflexively solved problem for human infants. And so the story continues all the way to the outer reaches of scientific discovery.

Well, and it may not be continuous. I'm not suggesting that; there's probably different capacities involved, rather like Hume. But Peirce concluded that humans must have what he called an 'abductive instinct,' which provides a limit on admissible hypotheses, so that only certain explanatory schemes can be entertained, but not infinitely many others, all compatible with available data. Peirce argued that this instinct develops through natural selection. That is, the variants that yield truths about the world provide a selectional advantage and are retained through descent with modification, Darwin's notions, while others fall away. That belief is completely unsustainable. It takes only a moment to show that that can't be true. And if you drop it, as we must, we're left with a serious and challenging scientific problem, namely to determine the innate components of our cognitive nature, those that are employed in reflexive identification of language-relevant data, or in other cognitive domains.

Take one famous case, the capacity of humans, which is quite remarkable — if presented with a sequence of two tachistoscopic presentations, just dots on a screen, three dots on a screen, presented with a sequence of these, what you perceive is a rigid object in motion. Some of the cognitive principles are known, but not the neural basis for or for example, discovering and comprehending Newton's laws, or developing string theory, or solving problems of quantum entanglement, or as complex as you like. And there is a further task, that's to determine the scope and limits of human understanding. Incidentally, some differently structured organism, some Martian, say, might regard human mysteries as simple problems, and might wonder that we can't find the answers, or even ask the right questions, just as we wonder about the inability of rats to run prime number mazes. It's not because of limits of memory or other superficial constraints, but because of the very design of our cognitive nature, and their cognitive nature.

So, actually, if you think it through, I think it's quite clear that Newton's remarkable achievements led to a significant lowering of the expectations of science, a severe restriction on the role of intelligibility. They furthermore demonstrated that it's an error to ridicule what's called the 'ghost in the machine.' That's what I, and others, were taught at your age, in the best graduate schools, Harvard, in my case. But that's just a mistake. Newton did not exorcise the ghost; rather, he exorcised the machine. He left the ghost completely intact. And by so doing, he inadvertently set the study of mind on a quite a new course, that made it possible to integrate it into the sciences.

And Newton may very well have realized this. Throughout his life, he struggled, in later life, struggled vainly, of course, with the paradoxes and conundrums that followed from his theory, and he speculated that what he called 'spirit,' which he couldn't identify, but whatever it is, might be the cause of all movement in nature, including the power of moving our body by our thoughts, and the same power within other living creatures. 'Though how this is done, and by what laws,' that, 'we do not know, that we cannot say,' he concluded. 'All nature is not alive.'

Going a step beyond Newton, Locke suggested that we cannot say that matter does not think. That's a speculation that's called 'Locke's suggestion' in the history of philosophy. So, as Locke put it, just as God had added to motion, inconceivable effects, 'it is not much more remote from our comprehension to conceive that God can, if he pleases, superadd to matter the faculty of thinking.' Locke found this view repugnant to the idea of senseless matter, but he said that we cannot reject it because of our incurable ignorance and the limits of our ideas. That is, our cognitive capacities. Having no intelligible concept of matter or physical, as we still don't, incidentally, but having no such concept, we, he said, we cannot dismiss the possibility of living or thinking matter, particularly after Newton had totally undermined common-sense understanding, permanently.

Locke's suggestion was understood, and it was taken up right through the 18th century. Hume concluded that motion may be, and actually is, the cause of our thought and perception. Others argued that since thought, which is produced in the brain, cannot exist if this organ is wanting, and since there's no reason any longer to question the existence of thinking matter, it's necessary to conclude that the brain is a special organ designed to produce thought, much as the stomach and the intestines are designed to operate the digestion, the liver to filter bile, and so on, through the bodily organs. So, just as foods enter the stomach and leave it with new qualities, so impressions arrive at the brain through the nerves, and are then isolated. They arrive isolated and without any coherence, but the organ, the brain, enters into action. It acts on them, sends them back changed into ideas, which the language of physiognomies and gesture or the signs of speech and writing manifest outwardly.

We conclude then, with the same certainty, that the brain 'digests,' as it were, the impressions, that is, organically it makes the 'secretion' of thought, just as the liver secretes bile. Darwin, who agreed with this view, put the matter succinctly. He asked rhetorically, 'Why is thought, being a secretion of the brain, more wonderful than gravity, a property of matter?' A property that we understand but just came to accept.

It's therefore rather odd to read today, what I quoted before, the leading thesis of the decade of the brain that ended the last century, namely, that things mental, indeed minds, are emergent properties of brains. Mountcastle's summary is strange to read because it was commonplace in the 18th century, so it's not clear why it's an emerging thesis. Many other prominent scientists and philosophers have presented essentially the same thesis as contemporary examples. The 'astonishing hypothesis' of the new biology, a radical new idea in the philosophy of mind, boldly asserts that mental phenomena are entirely natural and caused by the neurophysiological activities of the brain, opening the door to novel, promising inquiries and a rejection of Cartesian mind-body dualism, and so on. All of these reiterate, in virtually the same words, formulations of centuries ago.

The traditional mind-body problem, having become unformulable with the disappearance of the only coherent notion of body (again, physical, material, and so on), is exemplified by Joseph Priestley's 18th-century conclusion that properties termed mental reduce somehow to the 'organical structure of the brain,' an idea he developed in quite interesting ways. This idea was stated in different words, less detailed, by Hume, Darwin, and many others, and seems almost inescapable after the collapse of the mechanical philosophy.

Well, with the belated revival of ideas that were reasonably well understood centuries ago, and our direct conclusions from Newton's discoveries, we're left with scientific problems about the theory of mind. They can be pursued in many ways, like other questions of science, maybe with an eye to eventual unification, whatever form it may take, if any. This enterprise renews a task that Hume understood quite well. He called it 'the investigation of the science of human nature,' the search for the 'secret springs and principles by which the human mind is actuated in its operations,' including those parts of our knowledge that are derived from the 'original hand of nature,' so what we would call genetic endowment.

Hume you know, is the arch empiricist but also a dedicated nativist, supposed to be the opposite of empiricism, and he had to be because he was reasonable. This inquiry, which Hume compared in principle to Newton's, had in fact been undertaken in quite sophisticated ways by English Neoplatonists, work that directly influenced Kant. In contemporary literature, there are names for this, sometimes called 'naturalization of philosophy' or 'epistemology naturalized,' or sometimes just 'cognitive science.' But in fact, it's the direct consequence of Newton's demolition of the idea of grasping the nature of the world, and inescapable.

So, let me just summarize briefly. I think it's fair to conclude that the hopes and expectations of the early Scientific Revolution were dashed by Newton's discoveries, which leaves us with several conclusions. One conclusion, actually reinforced by Darwin, is that while our cognitive capacities may be vast in scope, they are nonetheless intrinsically limited. Some questions that we might like to explore may well lie beyond our cognitive reach; we may not even be able to formulate the right questions. The standards of success may have to be lowered once again, as has happened before. They varied dramatically with the collapse of the mechanical philosophy.

And another conclusion is that the mind-body problem can safely be put to rest, since there is no coherent alternative to Locke's suggestion. And if we adopt Locke's suggestion, that opens the way to the study of mind as a branch of biology, much like the study of the rest of the body, 'below the neck,' putting it metaphorically. A great deal has been learned in the past half-century, a revival of traditional concerns of the early Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment. But many of the early leading questions have not been answered and may never be.