machinesseekingconnections

2 years ago

Intensity

The concept of intensity in Gilles Deleuze's philosophy is multifaceted and central to his ontology, ethics, politics, and aesthetics. Here's a breakdown of the main aspects of intensity.

1. Ontological Foundation: In Deleuze's philosophy, "intensity" refers to the qualitative forces that constitute reality but are not themselves extended in space. These intensities are virtual—meaning they are real but not actualized in a tangible form—and they underpin the manifestation of all physical and observable phenomena. For example, consider the concept of temperature in a weather system: temperature itself is an intensive property that doesn't assume a visible shape but influences the formation and behavior of clouds and winds, thus shaping the extended forms of weather patterns that we can observe and measure. Deleuze challenges traditional metaphysics that prioritizes extension (things and their physical properties) over these more foundational intensities. His ontology posits that intensities are what generate the extended forms and qualities of the world we experience. This idea is rooted in his concept of "transcendental empiricism," which requires us to sense these underlying intensities that are not accessible through ordinary perception but through other faculties such as memory and imagination.

2. Difference and Becoming: Intensities are crucial in Deleuze's redefinition of difference. Unlike traditional views that see difference as comparative (i.e., something being different from something else), Deleuze understands difference as an intrinsic property of intensity. For instance, take the intensity of a musical note, which varies not only in pitch but in its emotional resonance and texture. Each variation, even within the same note played at different times or in different contexts, creates a unique event in experience, differing from its previous instances not by comparison but as a distinct occurrence. Intensities themselves are singularities that differ in themselves and from each other without reference to anything external. They cannot be subdivided or altered without changing their nature, which makes each intensity a unique event that fosters change and becoming.

3. Ethics and Politics: Intensity in Deleuze's ethics and politics relates to the potential to transform or become worthy of what he calls "the virtual event"—a significant, transformative force or occurrence that one must be prepared to encounter and engage with. Consider a social movement or a moment of personal revelation; these are examples of virtual events that carry intense transformative potential, pushing individuals to rethink values and behaviors. This involves an ethical and political dimension where individuals strive to increase their capacity for positive encounters that enhance their power and joy, aligning with the philosophical traditions of Stoicism, Nietzscheanism, and Spinozism. Through this process, individuals aim to not only adapt to these changes but to actively shape them, enhancing their ability to contribute to and thrive within these new realities.

4. Aesthetics: In Deleuze's aesthetic theory, intensity shifts focus from traditional forms to sensations, which are direct experiences of forces. Consider an abstract painting that does not depict a recognizable scene but evokes powerful emotions through its colors, shapes, and textures. These elements in the painting are not mere representations but are dynamic interactions of forces that affect viewers and are affected by their interpretations, blurring the lines between the subject (viewer) and object (artwork). The artist, then, is someone who captures and expresses these intensities, creating works that enable others to experience the transformative power of these forces. Through their art, they invite viewers to engage with and be moved by the raw intensities of color and form, catalyzing personal and communal shifts in perception and emotion.

Overall, Deleuze’s concept of intensity challenges conventional ideas of being and perception by emphasizing the unseen forces that underlie and actualize all aspects of reality. It encourages a profound engagement with the world that goes beyond surface appearances to the dynamic interplay of forces that shape existence.

2 years ago

Singularity

In the concept developed by Gilles Deleuze, "singularity" represents a distinctive point or situation that is pivotal, unique, and serves as a catalyst for change and diversity. Deleuze's use of the term emerges against a historical backdrop where "singularity" originally replaced the notion of a "mirror" used in medieval representations of the world. While the medieval "mirror" depicted a totality reflecting a divine order, the concept of singularity arises with the age of exploration, which introduced new, often contradictory or unprecedented elements that demanded a different, more flexible, and open form of representation. For instance, when European explorers first documented their encounters with the unique wildlife of the Galápagos Islands, these observations challenged existing biological classifications and inspired new scientific theories. The singular nature of the Galápagos fauna, particularly its distinct species like the giant tortoises and finches, served as a pivotal catalyst for the development of evolutionary theory, exemplifying how a singularity can radically transform existing knowledge systems and perceptions.

Deleuze applies "singularity" to describe points of high importance or intensity within a context, where conventional perceptions and experiences are disrupted, leading to new forms of understanding and expression. These points are not fixed; rather, they are dynamic, open to continuous revision and interpretation—what Deleuze terms "open totalities." For example, in the context of art, the Dada movement of the early 20th century can be seen as a singularity. It emerged in response to the horrors of World War I, challenging traditional aesthetics and cultural norms through its embrace of absurdity, randomness, and anti-art elements. This movement disrupted the conventional art scene dramatically, leading to new forms of artistic expression and laying the groundwork for later avant-garde movements like Surrealism. The Dada movement exemplifies how a singularity can destabilize existing structures and open up new possibilities for creativity and interpretation.

Singularity, in a broader philosophical sense for Deleuze, pertains to the unique characteristics of an event or entity that differentiate it from others, enabling novel perceptions and interactions. It is similar to how islands, as distinct entities, create unique interactions with their surroundings. These singular points can influence perceptions both minutely and vastly, allowing a person to experience the world in multifaceted ways—both "infinitesimally" and "infinitely." For instance, the phenomenon of witnessing a solar eclipse can be considered a singularity. This rare event offers a unique and profound experience that alters our usual perceptions of the daytime sky, encouraging both awe and a deeper scientific inquiry into the workings of our solar system. The singular experience of an eclipse, visible only from specific locations on Earth, not only impacts the individuals who observe it but also stimulates broader discussions and studies about celestial mechanics and the nature of the cosmos. This shows how a singularity can provide a powerful moment of connection and transformation, influencing both individual perceptions and collective knowledge.

In civic geography, for instance, a singularity could be a specific geographical feature that defines or characterizes a region, influencing how it is perceived and interacted with. In the realm of creativity and literature, singularity enables writers to transform standard perceptions into unique, impactful visions, thereby altering language and influencing readers' views of the world.

Thus, Deleuze’s concept of singularity encompasses a broad range of applications, from the geographical and the perceptual to the philosophical and the creative, emphasizing the transformative potential of unique, distinct points in forming and re-forming our understanding of the world.

2 years ago

Some Deleuzian Concepts

These were generated by Chat GPT

Event

Imagine a dance floor where a dance (the event) emerges from the interactions of the dancers, the music, and the environment. No single element (like just the music or just one dancer) can create the dance. It happens because all these elements come together in a specific way at a specific time. This interaction is what Deleuze means by an ‘event’. It’s not just the movements (what we see), but the energy and interactions that make those movements possible.

In Deleuze’s view, events are like hidden recipes that make certain outcomes possible. They are potentialities that only become visible when they unfold. Take the example of a tree turning green in spring. What we see is the green tree, but the ‘event’ includes all the unseen factors like the soil quality, weather, and the tree’s biology, which interact to produce the greening. Instead of saying “the tree is green,” which makes it sound static and unchanging, saying “the tree greens” suggests this ongoing, dynamic process—a series of interactions becoming visible.

Deleuze challenges traditional ideas that focus on static states or essences of things. Instead of looking at the world as a set of fixed objects (like a series of snapshots), he sees it as a continuous flow of events, an ever-changing landscape where each moment is a blend of various forces coming together. This view emphasizes the fluidity and ongoing creativity of reality, where new potentials are always unfolding.

He also points out that events are unique and original. They don’t just follow a template or mimic something that came before. Each event is a fresh creation, like an artist painting a new scene rather than copying an old one.

Finally, in Deleuze’s philosophy, thinking itself is an event. It’s not just about processing or generating ideas; it’s about engaging dynamically with the world, being open to new possibilities and insights that emerge from the interplay of many forces and factors. This way of thinking challenges us to view life not as a series of static images but as a vibrant, ever-changing canvas.

Exteriority/Interiority

Gilles Deleuze’s concept of exteriority and interiority can be likened to thinking about how we understand a forest. Imagine you’re looking at a forest from a distance. You could think of the forest as having an “interior essence,” like a secret spirit or a definitive, unchanging character that defines what it is, regardless of what happens around it. This view, focusing on the interior essence of the forest, aligns with traditional Western philosophy, which often sees things (including people) as having a core, intrinsic nature or essence that explains their behavior and existence.

Deleuze, however, would argue that this traditional view is limiting and inaccurate. Instead of looking for some hidden essence or interior, Deleuze invites us to consider the forest entirely from the “outside.” This means seeing the forest in terms of the countless interactions and relationships it has with everything around it—the soil, the climate, the animals that live in it, and even the humans who interact with it. The forest, in Deleuze’s view, is its relationships; it doesn’t have a secretive, inner nature that’s detached from these external interactions.

In this metaphor, Deleuze would argue that nothing has a “natural interiority” (a natural, independent essence). What we often think of as the “interior” (like the spirit of the forest) is actually formed through the countless external interactions and relationships (the “exterior”). So, when you see a tree, you shouldn’t think of it as manifesting its inner essence but rather as something existing in a dynamic web of relationships—soil nutrients, water, sunlight, and more.

Therefore, in Deleuze’s philosophy, understanding anything—whether a forest, a person, or society—requires us to look at the external, interconnected relations and influences, not at some supposed intrinsic essence. This approach, which focuses on the exterior and sees the interior as a product of external relations, leads to a philosophical and ethical stance that emphasizes openness, interconnection, and the constant influence of our environment on what we are. This viewpoint encourages us to embrace the external world and our interdependence with it, rather than retreating into an imagined, isolated interior.

Sensation

Imagine you're walking into a bakery. Before you even see any pastries, the warm, rich aroma of freshly baked bread envelops you. This initial, direct experience is akin to what Deleuze refers to as "sensation." It's something you feel immediately and intensely, without needing to consciously think about it or even recognize it as the smell of bread. This sensation hits you before any cognitive recognition kicks in, like realizing "Ah, that’s the smell of bread baking!" This is a moment of pure sensation — it’s raw and direct.

Deleuze believes this kind of sensation is fundamental to how we experience the world and it’s a key aspect of perception. Perception here doesn't just mean recognizing and naming what we sense (like identifying the smell of bread), but it's also about how these sensations impact us and create experiences. For instance, that smell might evoke a memory of your grandmother’s kitchen or make you suddenly realize how hungry you are.

Applying this to art, when you look at a painting or hear a piece of music, the initial impact before you start to think about what it represents or means is what Deleuze calls sensation. For example, seeing a bold splash of red on a canvas might strike you immediately as intense or aggressive — that's sensation. It’s only after this that you might start to interpret the red as symbolizing anger or passion.

Deleuze uses the artwork of Francis Bacon as an example. Bacon's paintings often depict distorted, abstract figures that convey raw, emotional experiences. When you look at these images, the immediate feeling or mood they provoke happens before you begin to think about what the figures might represent or the story behind them.

Moreover, Deleuze talks about "the Body without Organs" (BwO) as a way of describing a state where sensation flows freely without the typical organization or hierarchy our bodies usually operate under. Think of it as experiencing life like a continuous stream of music, where you feel every note intensely and individually without necessarily thinking about the melody or the song structure.

Finally, sensation for Deleuze isn’t just a passive experience but something very active and dynamic. It involves a direct interaction between the perceiver and the world, where new meanings, events, and experiences are constantly being created. This ties back to his broader philosophy that everything is in a state of becoming and change, and our sensations are a crucial part of this dynamic process.

So, in essence, Deleuze's concept of sensation is about these immediate, powerful experiences that precede and shape our perceptions, influencing not just how we think but how we engage with and create our reality.

Affect

Gilles Deleuze's concept of affect can be tricky, but imagine it this way: affect is like the invisible force behind every experience before it fully forms into thoughts or emotions.

Let's break it down using simple metaphors:

1. The Color of a Sunset: Think of affect as the intensity of color in a sunset. It's not just any color, but the profound, moving quality it has even before you think, "Wow, that's beautiful!" It's the raw impact that color has on you, which might stir feelings or thoughts, but exists before any of that crystallizes into "I feel serene" or "I feel sad."

2. The Moment Before a Kiss: Affect is also like that electric moment just before a kiss. It's not about the kiss itself or even the anticipation you can describe, but rather the undetectable buildup of everything happening in your body and mind right before your lips touch another's. It's a pulse of potential that hasn't yet been defined by your senses.

3. A Ghost's Reaction: Imagine a ghost in a room that suddenly reacts when someone enters. Affect in this context is like the disturbance in the air or the shift in energy — something changes, but it's more about the transition than the visible effect. It's what happens to the atmosphere, not necessarily to the ghost or the person entering.

Deleuze is saying that affect is about these kinds of interactions and changes that occur when different things (bodies, objects, forces) come together. It's not just a feeling or an emotion but the process and effect of being affected.

For Deleuze, using the term affect helps us think about experiences in a fresh way:

- Not just emotional: It's not merely about feelings but about changes that can be physical, spiritual, or intellectual.

- Not passive: It's about active participation in life’s events, not just watching them passively.

- Before cognition and perception: Affect is what happens before we even start to understand or interpret what we're experiencing.

In essence, Deleuze wants us to see affect as a fundamental element of existence that drives how things develop and transform over time, shaping both our personal experiences and the world around us. This approach challenges traditional views that focus only on clear, definable emotions and thoughts, suggesting instead that life is a continuous flow of affects, transformations, and encounters.

Force

Deleuze’s concept of force can be a bit complex, but let’s break it down using a simple metaphor. Imagine a bustling city where everything and everyone is constantly moving and interacting—cars weaving through traffic, people mingling in cafes, and street performers interacting with crowds. This city represents the world, and each entity within it—a car, a person, a coffee cup—is a force.

In Deleuze’s view, inspired by Nietzsche, these forces don’t have a specific origin or end goal; they simply exist to interact in an ever-changing dance. They’re not trying to reach a final state of calm or balance; rather, they’re always in motion, always becoming something new. This ongoing process of transformation is what Deleuze calls ‘becoming’.

For Deleuze, a force isn’t something aggressive or pressurized; it’s any capacity to bring about change. This could be physical, like a gust of wind blowing papers off a table, or more abstract, like an idea sparking a movement or a change in societal norms.

The interactions between these forces are what shape reality. Every car’s path affects another’s; every conversation in a cafe alters the social atmosphere. Each of these interactions is an ‘event’—a unique outcome of forces clashing or cooperating in unpredictable ways.

Now, let’s add another layer. Forces can be ‘active’ or ‘reactive’. An active force is like a person who walks confidently through the crowd, influencing others’ paths with their presence. A reactive force, on the other hand, is like someone who hesitantly steps back into a doorway to avoid disrupting the flow.

In this bustling city, nothing is fixed. Every moment brings new arrangements of cars, people, and interactions, meaning no scene can ever be exactly repeated. The city, like the world in Deleuze’s view, has no permanent structures or essences; it is always in flux, composed only of these forces and their interactions.

Deleuze challenges traditional philosophical ideas that suggest things have an essence or a perfect, unchanging form. Instead, he suggests that everything we perceive is the result of complex, temporary interactions. Just as a pencil on a desk isn’t just an object, but part of a wider array of events including its material properties and its use in that moment, every element of reality is similarly complex and contingent.

So, in Deleuze’s philosophy, the world is less like a stable narrative with a clear beginning and end, and more like an improvisational dance, where every move influences the next, and nothing is predetermined.

Immanence

To explain Gilles Deleuze's concept of immanence in a simpler and more relatable way, let's use the metaphor of a fish swimming in an ocean.

Immanence vs. Transcendence:

Think of immanence like the fish swimming in the ocean. Everything it experiences, understands, and interacts with happens within the ocean. There's nothing "outside" it needs to refer to or rely on for its existence or understanding of the world—it’s all happening in an interconnected, inclusive space. This is Deleuze's idea of immanence: everything exists and functions within the same plane or realm, with nothing beyond or above it dictating its reality.

Now, think of transcendence as the idea that there's something beyond the ocean that the fish needs to refer to or depend upon—like a bird or a human looking at the ocean from the outside. In many traditional philosophies and religions, this is how things are seen: there is a higher realm or a divine being that everything in the "lower" realm (like our ocean) must relate to and is dependent on for meaning and existence. For example, in Christianity, the physical world is often seen as secondary to the spiritual realm of God.

Why Deleuze Favors Immanence:

Deleuze argues against this idea of transcendence because it creates a separation or a hierarchy where the "lower" realm is seen as lesser or incomplete on its own, needing the "higher" realm to give it value or meaning. He dislikes how this setup devalues our immediate, lived experiences (the fish's life in the ocean) by always pointing to something outside of it (like the bird or human observing the ocean).

How Deleuze Uses Immanence:

Deleuze uses the idea of immanence to suggest that everything is interconnected within the same "ocean," without needing an external force to give it meaning. He believes that life, understanding, and reality all unfold and exist within a shared, continuous realm. For example, he draws on Friedrich Nietzsche's idea of the "eternal return," which suggests that life's events and experiences continually recur but always in slightly different ways, showing that change and difference are the natural states of the world.

The Importance of Connection and Difference:

In this view, the focus is not on separating things into categories or ranks (like mind and body, or human and divine) but on seeing how they connect, change, and interact. Deleuze emphasizes how everything is fundamentally related and how new ideas and realities emerge from these connections, not from transcending them.

Critiques and Challenges:

While Deleuze's idea of immanence is compelling, it's also challenging and has been critiqued. Critics like Alain Badiou argue that Deleuze's concept of the "virtual" (the potential of things to become other than they are) is itself a kind of transcendence, because it points to a realm of possibility beyond actual reality. However, Deleuze would argue that this virtual aspect is inseparably connected to the actual, meaning they continually affect and redefine each other without one being superior to the other.

In sum, Deleuze’s philosophy is like saying that the life of the fish is complete within the ocean itself, without needing to refer to anything outside of it to find meaning or value. This perspective values the richness and complexity of our immediate world and our experiences within it.

Materialism

To explain Gilles Deleuze’s concept of materialism in a simplified way, let’s imagine a busy city where everything is constantly moving and changing. This city isn’t just made of buildings and roads, but includes air, sound, people, ideas, and even the invisible forces like gravity and energy. Everything in the city interacts in complex and often unpredictable ways.

Deleuze’s materialism views the world somewhat like this bustling city. He argues against traditional views that separate matter (like physical objects) from form (the shape or idea of those objects). Instead of thinking of the world as being made up of static objects molded into form, like clay pressed into a specific shape, Deleuze sees the world as a dynamic flow of matter that is always changing and evolving—more like a river constantly shaping and reshaping the landscape as it flows.

He was inspired by philosophers like Spinoza and Nietzsche, who emphasized the body and physical existence over the mind or consciousness, suggesting that our thoughts are part of the material world and not separate from it. They argued against putting too much emphasis on consciousness as something distinct from our bodies.

Adding to this, Deleuze introduces the idea of the “plane of consistency,” which is an abstract concept where everything exists together on a single level. On this plane, things are defined not by their shape or form but by their behavior and relationships—like how different parts of the city affect each other in various ways, through movement, energy, and interaction.

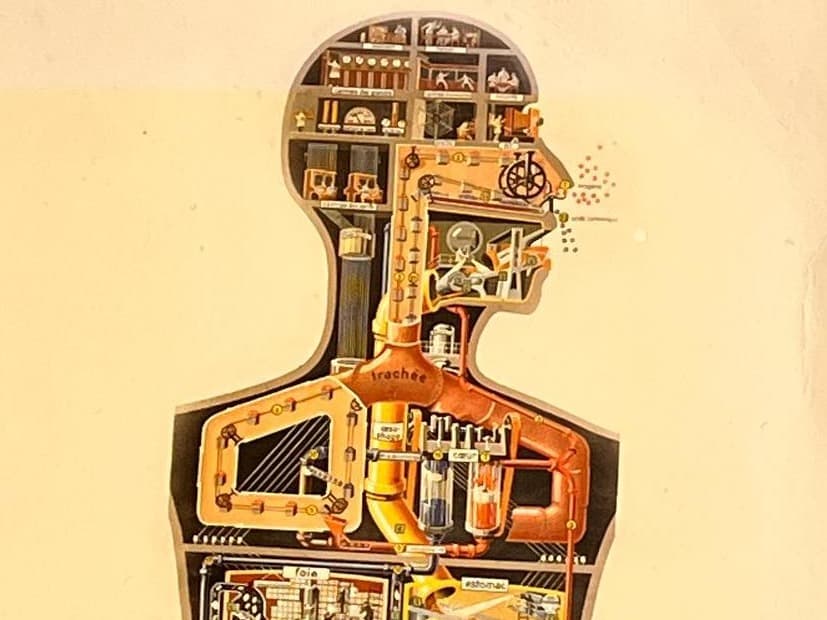

Deleuze also talks about “machines,” but not in the usual sense of physical devices. Instead, he imagines abstract machines, which are systems or networks of interaction that produce something new. These machines aren’t necessarily made of metal and gears but could be any kind of relationship that generates change, like the interaction between different ideas, or between technology and humans.

In his view, everything—including thoughts, technology, and art—can interact directly with our nervous systems, shaping how we think and perceive the world without necessarily needing a logical or digital code, like in computers.

Ultimately, Deleuze’s materialism is about seeing the world as an interconnected, dynamic flow of material interactions, where new possibilities for thought and existence are constantly being created. This approach moves away from breaking things down into simple parts (like atoms or molecules) and instead focuses on the rich tapestry of interactions that make up the reality we experience.

Expression

Imagine a vast art workshop filled with artists, each with an array of paints and canvases. In this workshop, there is no pre-defined idea that each artist must follow; instead, each artist creates whatever comes to mind, with each stroke of the brush revealing new possibilities and directions for their artwork. This ongoing creative process in the workshop represents life as Deleuze sees it—an expressive and open whole where new relationships and creations continuously emerge.

Now, let’s break down some key points using this metaphor:

1. Concept of Expression: In Deleuze’s philosophy, “expression” is not about simply describing or representing something that already exists. It’s more like how each artist in our workshop makes unique brush strokes on the canvas, constantly creating new forms and ideas. Expression is the dynamic process of unfolding life’s potential, just like each brush stroke brings a new aspect of the artist’s vision to life.

2. Life as an Expressive Whole: Instead of thinking about life as a series of set pieces and fixed terms (like a pre-drawn stencil that artists must color in), Deleuze views life as a canvas with endless possibilities. Each moment and each interaction are like strokes on this canvas, continuously evolving and bringing about new forms.

3. Concepts vs. Structures: In traditional philosophy, concepts might be seen as fixed structures—like a set of rules that govern how to paint or what the painting must look like. Deleuze challenges this by treating concepts like living, changing entities themselves. They are not static but are intensive and dynamic, much like how an evolving painting might inspire various emotions and interpretations.

In essence, Deleuze invites us to think of life and philosophy as an art workshop where creation and expression are continuous and boundless. Every action, thought, and interaction adds to this canvas, making life a never-ending artwork of possibilities.

Individuation

Imagine you have a lump of clay. Traditionally, we think of creating something (like a sculpture) by imposing a form onto this clay using a mold. This is similar to the old philosophical concept called “hylomorphism,” where things (individuals) are thought to emerge by fitting into pre-existing molds or forms (like species or types).

Deleuze criticizes this view because it suggests that individuals are just the final product of a molding process—a predetermined endpoint. Instead, he introduces a more dynamic process called “modulation,” where instead of a mold, the clay continuously changes shapes and forms in response to different pressures and touches. This is a process of constant transformation and adaptation, where the end result isn’t predefined.

The Process of Individuation

Now, imagine that our clay isn’t just physically being shaped, but is also undergoing changes on the inside. Deleuze says that individuation (the process of becoming an individual) involves both the visible changes and the internal dynamics that you can’t see. He distinguishes between:

• Differentiation: This is like the internal changes happening within the clay, based on the conditions it’s exposed to (like moisture, temperature). These conditions aren’t visible but affect how the clay behaves.

• Differenciation: This refers to the observable changes, like the actual shapes and forms the clay takes.

Virtual and Actual

Deleuze talks about two realms: the “virtual” and the “actual.” Using our clay analogy, think of the “virtual” as all the potential forms and states the clay could take, driven by internal and external forces. The “actual” is the specific form the clay takes at any given moment.

The process of moving from the virtual to the actual is driven by what Deleuze calls “intensity.” In our metaphor, intensity could be thought of as the energy or force applied to the clay that drives its transformation from just potential (virtual) to a specific shape (actual).

Haecceities: The Nature of Individuality

Deleuze introduces a term “haecceity,” which refers to the unique identity of an individual, not based on broad categories or types but on unique characteristics (like a specific level of heat or a certain time of day). Imagine each piece of clay having its own set of conditions and responses that make it unique, not just because of its shape but because of how it reacts to its environment.

These haecceities are like individual signatures in the clay—each one is different and unique, contributing to the overall identity of the sculpture not just through its form but through its interaction with the world around it.

Summary

In summary, Deleuze’s concept of individuation is about seeing each individual as a continuously evolving process, not just a static end product. It’s a dynamic interaction between the internal potentials and the external realities, where each individual is shaped and reshaped constantly, influenced by both visible and invisible forces. This process celebrates the uniqueness and creativity of becoming, rather than the conformity to pre-existing molds or categories.

Semiotics

1. Basics of Semiotics: Semiotics is the study of signs and symbols and how they create meaning. Think of it as trying to understand how different symbols (like words, traffic signs, or even clothes) convey information and meaning to those who interpret them.

2. Deleuze and Guattari's Approach: Unlike traditional semiotics, which often looks at signs as having a fixed meaning (like a red traffic light means stop), Deleuze and Guattari see meanings as more fluid and open to interpretation. They argue that both content and expression are not fixed entities but are part of a larger, dynamic system. Imagine a conversation where not just the words but the tone, the context, and even the location are all interacting to create a unique meaning each time.

3. Triadic Semiotics: They move away from the traditional binary model of signifier (the form of the word) and signified (the concept it represents), adopting instead a triadic model. This third element introduces a level of interpretation that makes the relationship between signs much more dynamic and fluid, similar to adding a live audience to a performance, which changes the dynamic of the show.

4. Diagrams and Maps: Deleuze and Guattari use the metaphor of a diagram or a map, which doesn't just represent a territory but actively participates in its creation. So, instead of thinking of a map as a static picture of streets and landmarks, imagine it as a tool that can create or transform the physical and social landscape it depicts.

5. Beyond Words: Their concept of semiotics extends beyond linguistic signs to include images, memories, and even emotions, which are understood not in isolation but as part of a network or web of meanings. This is akin to understanding a city not just by its street signs but by its smells, sounds, and the feelings it evokes.

6. Semiotics of Life: They see signs everywhere—in art, in literature, in everyday life—and these signs are "symptoms" of life's vibrant and dynamic nature. Understanding these signs involves engaging with the world in a way that is always open to new interpretations and possibilities.

7. Philosophical Implications: For Deleuze and Guattari, philosophy itself becomes a process of creating and engaging with signs and meanings, not to pin down and define things rigidly but to open up more possibilities for thought and existence.

In essence, Deleuze and Guattari's semiotics is about seeing the world as a continuously shifting tapestry of meanings where everything is interconnected and nothing is fixed. This approach invites us to engage with the world more creatively and open-mindedly, looking for the deeper connections and possibilities that lie beneath the surface.

Power

Imagine power not as something that someone has over someone else, like a boss over an employee, but as an inherent energy or potential within every being or thing. This is similar to thinking of a plant’s power as its potential to grow, flower, and spread seeds. This potential is not just about growing up but expressing all the ways a plant can interact and change its environment.

Deleuze, inspired by philosophers like Spinoza and Nietzsche, sees power as something positive and creative. For Spinoza, every being strives to maintain and enhance its existence, much like a plant stretching toward the sun. This striving isn't about reaching a predetermined shape or size but about continually exploring and expressing its capabilities, which is a joyful process for the plant.

Nietzsche took this idea further by suggesting that beings don’t just have power—they are clusters of forces interacting with other clusters. For instance, a garden isn’t just a collection of individual plants with fixed roles; each plant affects and is affected by its surroundings, like soil, insects, and other plants, constantly changing the dynamics of the garden.

In this view, relationships between things (like plants in the garden) are more important than the things themselves. The nature of a plant is defined not just by its seeds or leaves but by its interactions—how it competes for sunlight, shares space, and even how it might support or hinder other plants.

Deleuze argues that understanding our world requires us to focus on these dynamic interactions and potentials, rather than on static entities. So, instead of seeing the world as a stage where pre-existing characters act out their roles, we should see it as a lively playground where characters can change, relationships evolve, and new stories can be written at any moment.

Ethically, Deleuze makes a distinction between active and reactive powers. Active powers reach out, explore, and maximize their potential, like a vine growing, twisting, and turning in search of light. Reactive powers, on the other hand, withdraw and limit themselves, like a plant that stops growing because it’s in the shade.

Politically, traditional views of power think about organizing people who already exist into systems. Deleuze challenges us to rethink this: it's not about managing what already exists but about unleashing and redirecting energies and potential to create new ways of living together, just as gardeners might introduce new plants or rearrange their gardens to create a more vibrant ecosystem.

In summary, Deleuze invites us to look at the world not as a collection of static beings with fixed powers but as a dynamic interplay of creative energies that define what beings can become. This perspective shifts how we understand power from something that is imposed or held over others to something inherent within every interaction and relationship, always capable of bringing about new and unexpected changes.

Micropolitics

Deleuze and Guattari's concept of micropolitics can be understood by contrasting it with more traditional forms of politics, which they refer to as "molar." Think of molar politics like a traditional garden with neatly arranged flower beds—everything is organized, predictable, and controlled. In this garden, plants (or societal elements) are strictly managed and everything must fit a pre-determined pattern or structure.

In contrast, micropolitics is like a wild, sprawling meadow where plants grow freely in natural patterns, without a central organizing principle. This wild meadow represents a more fluid, dynamic approach to societal organization where local, spontaneous interactions can occur. These interactions are not dictated by a rigid external structure but are self-organizing—like how in nature, ecosystems regulate themselves without any external control.

Micropolitics becomes necessary in what Deleuze and Guattari describe as "societies of control," where capitalism pervades all aspects of life, making traditional, rigid political structures (the neat garden) increasingly irrelevant. In these societies, the lines between private and public, individual and societal become blurred as everything is driven by the need to generate capital. This capital-driven society resembles a meadow taken over by a few aggressive species that spread everywhere, impacting the growth patterns of all other plants.

In this setting, micropolitics is about creating new ways of connecting and organizing—like planting new species in the meadow that can coexist with or even curb the aggressive spread of the dominant ones. It focuses on leveraging individual desires and local conditions to form new, productive connections and alliances, rather than relying on traditional, top-down control mechanisms.

These new connections are termed "desiring machines" by Deleuze and Guattari. They are not literal machines but metaphorical ones—networks of interactions and relationships that redirect and reshape desires and energies within the society to create something novel and dynamic. They challenge the status quo and promote ongoing change and evolution in society, avoiding the stagnation that comes from repetitive, unproductive patterns.

Thus, micropolitics is about fostering a continuous state of becoming and transformation, creating new ways of living together that are not bound by outdated societal structures or the homogeneous demands of capitalist production. It's an ethos of continuous revolution and adaptation, always forming new solidarities and dismantling old, restrictive ones.

2 years ago

Vibrant Matter

A space for people in the Vibrant Matter discussion group to post thoughts, questions, etc.

2 years ago

Ordinary Affects

A space for people in the Ordinary Affects discussion group to post thoughts, questions, etc.

2 years ago

Atmospheric attunements by Kathleen Stewart

https://drive.google.com/file/d/11H1jsXuWIxNZXhX5A8Uc5HWrhbdYmNZS/view?usp=sharing

2 years ago

Embodiment as a Paradigm for Anthropology

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1SZ_3I8vHqKFpBjgD4g8VQeRyApcbvhbj/view?usp=sharing

2 years ago

Narrative empathy

Narrative empathy refers to the ability of individuals to understand and share the feelings and experiences of characters within a narrative. It involves putting oneself in the shoes of the characters, imagining their perspectives, and emotionally connecting with their struggles, joys, and challenges.

Narrative empathy does not necessarily translate to genuine care or concern for people. It's possible for individuals to feel empathy towards characters in a news story without fully comprehending the complexities of the situation or the broader systemic issues at play. This can lead to a superficial understanding of the issues and a limited capacity for meaningful action or change.

Genuine care for people requires not just empathy, but also informed action and advocacy for positive change.

2 years ago

Self Writing

These pages are part of a series of studies on “the arts of oneself,” that is, on the aesthetics of existence and the government of oneself and of others in Greco-Roman culture during the first two centuries of the empire.

The Vita Antonii of Athanasius presents the written notation of actions and thoughts as an indispensable element of the ascetic life. “Let this observation be a safeguard against sinning: let us each note and write down our actions and impulses of the soul as though we were to report them to each other; and you may rest assured that from utter shame of becoming known we shall stop sinning and entertaining sinful thoughts altogether. Who, having sinned, would not choose to lie, hoping to escape detection? Just as we would not give ourselves to lust within sight of each other, so if we were to write down our thoughts as if telling them to each other, we shall so much the more guard ourselves against foul thoughts for shame of being known. Now, then, let the written account stand for the eyes of our fellow ascetics, so that blushing at writing the same as if we were actually seen, we may never ponder evil. Molding ourselves in this way, we shall be able to bring our body into subjection, to please the Lord and to trample under foot the machinations of the Enemy.” Here, writing about oneself appears clearly in its relationship of complementarity with reclusion: it palliates the dangers of solitude; it offers what one has done or thought to a possible gaze; the fact of obliging oneself to write plays the role of a companion by giving rise to the fear of disapproval and to shame. Hence, a first analogy can be put forward: what others are to the ascetic in a community, the notebook is to the recluse. But, at the same time, a second analogy is posed, one that refers to the practice of ascesis as work not just on actions but, more precisely, on thought: the constraint that the presence of others exerts in the domain of conduct, writing will exert in the domain of the inner impulses of the soul. In this sense, it has a role very close to that of confession to the director, about which John Cassian will say, in keeping with Evagrian spirituality, that it must reveal, without exception, all the impulses of the soul (omnes cogitationes). Finally, writing about inner impulses appears, also according to Athanasius’s text, as a weapon in spiritual combat. While the Devil is a power who deceives and causes one to be deluded about oneself (fully half of the Vita Antonii is devoted to these ruses), writing constitutes a test and a kind of touchstone: by bringing to light the impulses of thought, it dispels the darkness where the enemy’s plots are hatched. This text—one of the oldest that Christian literature has left us on the subject of spiritual writing—is far from exhausting all the meanings and forms the latter will take on later. But one can focus on several of its features that enable one to analyze retrospectively the role of writing in the philosophical cultivation of the self just before Christianity: its close link with companionship, its application to the impulses of thought, its role as a truth test. These diverse elements are found already in Seneca, Plutarch, Marcus Aurelius, but with very different values and following altogether different procedures.

No technique, no professional skill can be acquired without exercise; nor can the art of living, the tekhnē tou biou, be learned without an askēsis that should be understood as a training of the self by oneself. This was one of the traditional principles to which the Pythagoreans, the Socratics, the Cynics had long attached a great importance. It seems that, among all the forms taken by this training (which included abstinences, memorizations, self-examinations, meditations, silence, and listening to others), writing— the act of writing for oneself and for others—came, rather late, to play a considerable role. In any case, the texts from the imperial epoch relating to practices of the self placed a good deal of stress on writing. It is necessary to read, Seneca said, but also to write. And Epictetus, who offered an exclusively oral teaching, nonetheless emphasizes several times the role of writing as a personal exercise: one should “meditate” (meletan), write (graphein), train oneself (gumnazein): “May these be my thoughts, these my studies, writing or reading, when death comes upon me.” Or further: “Let these thoughts be at your command [prokheiron] by night and day: write them, read them, talk of them, to yourself and to your neighbor ... if some so-called undesirable event should befall you, the first immediate relief to you will be that it was not unexpected.” In these texts by Epictetus, writing appears regularly associated with “meditation,” with that exercise of thought on itself that reactivates what it knows, calls to mind a principle, a rule, or an example, reflects on them, assimilates them, and in this manner prepares itself to face reality. Yet one also sees that writing is associated with the exercise of thought in two different ways. One takes the form of a linear “series”: it goes from meditation to the activity of writing and from there to gumnazein, that is, to training and trial in a real situation —a labor of thought, a labor through writing, a labor in reality. The other is circular: the meditation precedes the notes which enable the rereading which in turn reinitiates the meditation. In any case, whatever the cycle of exercise in which it takes place, writing constitutes an essential stage in the process to which the whole askēsis leads: namely, the fashioning of accepted discourses, recognized as true, into rational principles of action. As an element of self-training, writing has, to use an expression that one finds in Plutarch, an ethopoietic function: it is an agent of the transformation of truth into ethos.

This ethopoietic writing, such as it appears through the documents of the first and the second centuries, seems to have lodged itself outside of two forms that were already well known and used for other purposes: the hupomnēmata and the correspondence.

THE HUPOMNĒMATA

Hupomnēmata, in the technical sense, could be account books, public registers, or individual notebooks serving as memory aids. Their use as books of life, as guides for conduct, seems to have become a common thing for a whole cultivated public. One wrote down quotes in them, extracts from books, examples, and actions that one had witnessed or read about, reflections or reasonings that one had heard or that had come to mind. They constituted a material record of things read, heard, or thought, thus offering them up as a kind of accumulated treasure for subsequent rereading and meditation. They also formed a raw material for the drafting of more systematic treatises, in which one presented arguments and means for struggling against some weakness (such as anger, envy, gossip, flattery) or for overcoming some difficult circumstance (a grief, an exile, ruin, disgrace). Thus, when Fundamus requests advice for struggling against the agitations of the soul, Plutarch at that moment does not really have the time to compose a treatise in the proper form, so he will send him, in their present state, the hupomnēmata he had written himself on the theme of the tranquility of the soul; at least this is how he introduces the text of the Perieuthumias. Feigned modesty? Doubtless this was a way of excusing the somewhat disjointed character of the text, but the gesture must also be seen as an indication of what these notebooks were—and of the use to make of the treatise itself, which kept a little of its original form.

These hupomnēmata should not be thought of simply as a memory support, which might be consulted from time to time, as occasion arose; they are not meant to be substituted for a recollection that may fail. They constitute, rather, a material and a framework for exercises to be carried out frequently: reading, rereading, meditating, conversing with oneself and with others. And this was in order to have them, according to the expression that recurs often, prokheiron, ad manum, in promptu. “Near at hand,” then, not just in the sense that one would be able to recall them to consciousness, but that one should be able to use them, whenever the need was felt, in action. It is a matter of constituting a logos bioēthikos for oneself, an equipment of helpful discourses, capable—as Plutarch says—of elevating the voice and silencing the passions like a master who with one word hushes the growling of dogs. And for that they must not simply be placed in a sort of memory cabinet but deeply lodged in the soul, “planted in it,” says Seneca, and they must form part of ourselves: in short, the soul must make them not merely its own but itself. The writing of the hupomnēmata is an important relay in this subjectivation of discourse.

However personal they may be, these hupomnēmata ought not to be understood as intimate journals or as those accounts of spiritual experience (temptations, struggles, downfalls, and victories) that will be found in later Christian literature. They do not constitute a “narrative of oneself”; they do not have the aim of bringing to the light of day the arcana conscientiae, the oral or written confession of which has a purificatory value. The movement they seek to bring about is the reverse of that: the intent is not to pursue the unspeakable, nor to reveal the hidden, nor to say the unsaid, but on the contrary to capture the already-said, to collect what one has managed to hear or read, and for a purpose that is nothing less than the shaping of the self.

The hupomnēmata need to be resituated in the context of a tension that was very pronounced at the time. Inside a culture strongly stamped by traditionality, by the recognized value of the already-said, by the recurrence of discourse, by “citational” practice under the seal of antiquity and authority, there developed an ethic quite explicitly oriented by concern for the self toward objectives defined as: withdrawing into oneself, getting in touch with oneself, living with oneself, relying on oneself, benefiting from and enjoying oneself. Such is the aim of the hupomnēmata: to make one’s recollection of the fragmentary logos, transmitted through teaching, listening, or reading, a means of establishing a relationship of oneself with oneself, a relationship as adequate and accomplished as possible. For us, there is something paradoxical in all this: how could one be brought together with oneself with the help of a timeless discourse accepted almost everywhere? In actual fact, if the writing of hupomnēmata can contribute to the formation of the self through these scattered logoi, this is for three main reasons: the limiting effects of the coupling of writing with reading, the regular practice of the disparate that determines choices, and the appropriation which that practice brings about.

1. Seneca stresses the point: the practice of the self involves reading, for one could not draw everything from one’s own stock or arm oneself by oneself with the principles of reason that are indispensable for self-conduct: guide or example, the help of others is necessary. But reading and writing must not be dissociated; one ought to “have alternate recourse” to these two pursuits and “blend one with the other.” If too much writing is exhausting (Seneca is thinking of the demands of style), excessive reading has a scattering effect: “In reading of many books is distraction.” By going constantly from book to book, without ever stopping, without returning to the hive now and then with one’s supply of nectar—hence without taking notes or constituting a treasure store of reading—one is liable to retain nothing, to spread oneself across different thoughts, and to forget oneself. Writing, as a way of gathering in the reading that was done and of collecting one’s thoughts about it, is an exercise of reason that counters the great deficiency of stultitia, which endless reading may favor. Stultitia is defined by mental agitation, distraction, change of opinions and wishes, and consequently weakness in the face of all the events that may occur; it is also characterized by the fact that it turns the mind toward the future, makes it interested in novel ideas, and prevents it from providing a fixed point for itself in the possession of an acquired truth. The writing of hupomnēmata resists this scattering by fixing acquired elements, and by constituting a share of the past, as it were, toward which it is always possible to turn back, to withdraw. This practice can be connected to a very general theme of the period; in any case, it is common to the moral philosophy of the Stoics and that of the Epicureans—the refusal of a mental attitude turned toward the future (which, due to its uncertainty, causes anxiety and agitation of the soul) and the positive value given to the possession of a past that one can enjoy to the full and without disturbance. The hupomnēmata contribute one of the means by which one detaches the soul from concern for the future and redirects it toward contemplation of the past.

2. Yet while it enables one to counteract dispersal, the writing of the hupomnēmata is also (and must remain) a regular and deliberate practice of the disparate. It is a selecting of heterogeneous elements. In this, it contrasts with the work of the grammarian, who tries to get to know an entire work or all the works of an author; it also conflicts with the teaching of professional philosophers who subscribe to the doctrinal unity of a school. It does not matter, says Epictetus, whether one has read all of Zeno or Chrysippus; it makes little difference whether one has grasped exactly what they meant to say, or whether one is able to reconstruct their whole argument. The notebook is governed by two principles, which one might call “the local truth of the precept” and “its circumstantial use value.” Seneca selects what he will note down for himself and his correspondents from one of the philosophers of his own sect, but also from Democritus and Epicurus. The essential requirement is that he be able to consider the selected sentence as a maxim that is true in what it asserts, suitable in what it prescribes, and useful in terms of one’s circumstances. Writing as a personal exercise done by and for oneself is an art of disparate truth—or, more exactly, a purposeful way of combining the traditional authority of the already-said with the singularity of the truth that is affirmed therein and the particularity of the circumstances that determine its use. “So you should always read standard authors; and when you crave a change, fall back upon those whom you read before. Each day acquire something that will fortify you against poverty, against death, indeed against other misfortunes as well; and after you have run over many thoughts, select one to be thoroughly digested that day. This is my own custom; from the many things which I have read, I claim some part for myself. The thought for today is one which I discovered in Epicurus; for I am wont to cross over even to the enemy’s camp,—not as a deserter, but as a scout [tanquam explorator].”

3. This deliberate heterogeneity does not rule out unification. But the latter is not implemented in the art of composing an ensemble; it must be established in the writer himself, as a result of the hupomnēmata, of their construction (and hence in the very act of writing) and of their consultation (and hence in their reading and their rereading). Two processes can be distinguished. On the one hand, it is a matter of unifying these heterogeneous fragments through their subjectivation in the exercise of personal writing. Seneca compares this unification, according to quite traditional metaphors, with the bee’s honey gathering, or the digestion of food, or the adding of numbers forming a sum: “We should see to it that whatever we have absorbed should not be allowed to remain unchanged, or it will be no part of us. We must digest it; otherwise it will merely enter the memory and not the reasoning power [in memoriam non in ingenium]. Let us loyally welcome such foods and make them our own, so that something that is one may be formed out of many elements, just as one number is

formed of several elements.” The role of writing is to constitute, along with all that reading has constituted, a “body” (quicquid lectione collection est, stilus redigat in corpus). And this body should be understood not as a body of doctrine but, rather—following an often-evoked metaphor of digestion—as the very body of the one who, by transcribing his readings, has appropriated them and made their truth his own: writing transforms the thing seen or heard “into tissue and blood” (in vires et in sanguinem). It becomes a principle of rational action in the writer himself.

Yet, conversely, the writer constitutes his own identity through this recollection of things said. In this same Letter 84—which constitutes a kind of short treatise on the relations between reading and writing—Seneca dwells for a moment on the ethical problem of resemblance, of faithfulness and originality. One should not, he explains, reshape what one retains from an author in such a way that the latter might be recognized; the idea is not to constitute, in the notes that one takes and in the way one restores what one has read through writing, a series of “portraits,” recognizable but “lifeless” (Seneca is thinking here of those portrait galleries by which one certified his birth, asserted his status, and showed his identity through reference to others). It is one’s own soul that must be constituted in what one writes; but, just as a man bears his natural resemblance to his ancestors on his face, so it is good that one can perceive the filiation of thoughts that are engraved in his soul. Through the interplay of selected readings and assimilative writing, one should be able to form an identity through which a whole spiritual genealogy can be read. In a chorus there are tenor, bass, and baritone voices, men’s and women’s tones: “The voices of the individual singers are hidden; what we hear is the voices of all together ... I would have my mind of such a quality as this; it should be equipped with many arts, many precepts, and patterns of conduct taken from many epochs of history; but all should blend harmoniously into one.”

CORRESPONDENCE

Notebooks, which in themselves constitute personal writing exercises, can serve as raw material for texts that one sends to others. In return, the missive, by definition a text meant for others, also provides occasion for a personal exercise. For, as Seneca points out, when one writes one reads what one writes, just as in saying something one hears oneself saying it. The letter one writes acts, through the very action of writing, upon the one who addresses it, just as it acts through reading and rereading on the one who receives it. In this dual function, correspondence is very close to the hupomnēmata, and its form is often very similar. Epicurean literature furnishes examples of this. The text known as the “Letter to Pythocles” begins by acknowledging receipt of a letter in which the student has expressed his affection for the teacher and has made an effort to “recall the [Epicurean] arguments” enabling one to attain happiness; the author of the reply gives his endorsement: the attempt was not bad; and he sends in return a text—a summary of Epicurus’s Peri phuseōs—that should serve Pythocles as material for memorization and as a support for his meditation.

Seneca’s letters show an activity of direction brought to bear, by a man

who is aged and already retired, on another who still occupies important public offices. But in these letters, Seneca does not just give him advice and comment on a few great principles of conduct for his benefit. Through these written lessons, Seneca continues to exercise himself, according to two principles that he often invokes: it is necessary to train oneself all one’s life, and one always needs the help of others in the soul’s labor upon itself. The advice he gives in Letter 7 constitutes a description of his own relations with Lucilius. There he characterizes the way in which he occupies his retirement with the twofold work he carries out at the same time on his correspondent and on himself: withdrawing into oneself as much as possible; attaching oneself to those capable of having a beneficial effect on oneself; opening one’s door to those whom one hopes to make better—“The process is mutual; for men learn while they teach.”

The letter one sends in order to help one’s correspondent—advise him, exhort him, admonish him, console him—constitutes for the writer a kind of training: something like soldiers in peacetime practicing the manual of arms, the opinions that one gives to others in a pressing situation are a way of preparing oneself for a similar eventuality. For example, Letter 99 to Lucilius: it is in itself the copy of another missive that Seneca had sent to Marullus, whose son had died some time before. The text belongs to the “consolation” genre: it offers the correspondent the “logical” arms with which to fight sorrow. The intervention is belated, since Marullus, “shaken by the blow,” had a moment of weakness and “lapsed from his true self”; so, in that regard, the letter has an admonishing role. Yet for Lucilius, to whom it is also sent, and for Seneca who writes it, it functions as a principle of reactivation—a reactivation of all the reasons that make it possible to overcome grief, to persuade oneself that death is not a misfortune (neither that of others nor one’s own). And, with the help of what is reading for the one, writing for the other, Lucilius and Seneca will have increased their readiness for the case in which this type of event befalls them. The consolatio that should assist and correct Marullus is at the same time a useful praemeditatio for Lucilius and Seneca. The writing that aids the addressee arms the writer—and possibly the third parties who read it.

Yet it also happens that the soul service rendered by the writer to his correspondent is handed back to him in the form of “return advice”; as the person being directed progresses, he becomes more capable, in his turn, of giving opinions, exhortations, words of comfort to the one who has undertaken to help him. The direction does not remain one-way for long; it serves as a context for exchanges that help it become more egalitarian. Letter 34 already signals this movement, starting from a situation in which Seneca could nonetheless tell his correspondent: “I claim you for myself ... I exhorted you, I applied the goad and did not permit you to march lazily, but roused you continually. And now I do the same; but by this time I am now cheering on one who is in the race and so in turn cheers me on.” And in the following letter, he evokes the reward for perfect friendship, in which each of the two will be for the other the continuous support, the inexhaustible help, that will be mentioned in Letter 109: “Skilled wrestlers are kept up to the mark by practice; a musician is stirred to action by one of equal proficiency. The wise man also needs to have his virtues kept in action; and as he prompts himself to do things, so he is prompted by another wise man.”

Yet despite all these points in common, correspondence should not be regarded simply as an extension of the practice of hupomnēmata. It is something more than a training of oneself by means of writing, through the advice and opinions one gives to the other: it also constitutes a certain way of manifesting oneself to oneself and to others. The letter makes the writer “present” to the one to whom he addresses it. And present not simply through the information he gives concerning his life, his activities, his successes and failures, his good luck or misfortunes; rather, present with a kind of immediate, almost physical presence. “I thank you for writing to me so often; for you are revealing yourself to me [te mihi ostendis] in the only way you can. I never receive a letter from you without being in your company forthwith. If the pictures of our absent friends are pleasing to us ... how much more pleasant is a letter, which brings us real traces, real evidence of an absent friend! For that which is sweetest when we meet face to face is afforded by the impress of a friend’s hand upon his letter—recognition.”

To write is thus to “show oneself,” to project oneself into view, to make one’s own face appear in the other’s presence. And by this it should be understood that the letter is both a gaze that one focuses on the addressee (through the missive he receives, he feels looked at) and a way of offering oneself to his gaze by what one tells him about oneself. In a sense, the letter sets up a face-to-face meeting. Moreover Demetrius, explaining in De elocutione what the epistolary style should be, stressed that it could only be a “simple” style, free in its composition, spare in its choice of words, since in it each one should reveal his soul. The reciprocity that correspondence establishes is not simply that of counsel and aid; it is the reciprocity of the gaze and the examination. The letter that, as an exercise, works toward the subjectivation of true discourse, its assimilation and its transformation as a “personal asset,” also constitutes, at the same time, an objectification of the soul. It is noteworthy that Seneca, commencing a letter in which he must lay out his daily life to Lucilius, recalls the moral maxim that “we should live as if we lived in plain sight of all men,” and the philosophical principle that nothing of ourselves is concealed from god who is always present to our souls. Through the missive, one opens oneself to the gaze of others and puts the correspondent in the place of the inner god. It is a way of giving ourselves to that gaze about which we must tell ourselves that it is plunging into the depths of our heart (in pectis intimum introspicere) at the moment we are thinking.

The work the letter carries out on the recipient, but is also brought to bear on the writer by the very letter he sends, thus involves an “introspection”; but the latter is to be understood not so much as a decipherment of the self by the self as an opening one gives the other onto oneself. Still, we are left with a phenomenon that may be a little surprising, but which is full of meaning for anyone wishing to write a history of the cultivation of the self: the first historical developments of the narrative of the self are not to be sought in the direction of the “personal notebooks,” the hupomnēmata, whose role is to enable the formation of the self out of the collected discourse of others; they can be found, on the other hand, in the correspondence with others and the exchange of soul service. And it is a fact that in the correspondence of Seneca with Lucilius, of Marcus Aurelius with Fronto, and in certain of Pliny’s letters, one sees a narrative of the self develop that is very different from the one that could be found generally in Cicero’s letters to his acquaintances: the latter involved accounting for oneself as a subject of action (or of deliberation for action) in connection with friends and enemies, fortunate and unfortunate events. In Seneca and Marcus Aurelius, occasionally in Pliny as well, the narrative of the self is the account of one’s relation to oneself; there one sees two elements stand out clearly, two strategic points that will later become the privileged objects of what could be called the writing of the relation to the self: the interferences of soul and body (impressions rather than actions), and leisure activity (rather than external events); the body and the days.

1. Health reports traditionally are part of the correspondence. But they gradually increased in scope to include detailed description of the bodily sensations, the impressions of malaise, the various disorders one might have experienced. Sometimes one seeks to introduce advice on regimen that one judges useful to one’s correspondent. Sometimes, too, it is a question of recalling the effects of the body on the soul, the reciprocal action of the latter, or the healing of the former resulting from the care given to the latter. For example, the long and important Letter 78 to Lucilius: it is devoted for the most part to the problem of the “good use” of illnesses and suffering; but it opens with the recollection of a grave illness that Seneca had suffered

in his youth, which was accompanied by a moral crisis. Seneca relates that he also experienced, many years before, the “catarrh,” the “short attacks of fever” Lucilius complains of: “I scorned it in its early stages. For when I was still young, I could put up with hardships and show a bold front to illness. But I finally succumbed, and arrived at such a state that I could do nothing but snuffle, reduced as I was to the extremity of thinness. I often entertained the impulse of ending my life then and there; but the thought of my kind old father kept me back.” And what cured him were the remedies of the soul. Among them, the most important were his friends, who “helped me greatly towards good health; I used to be comforted by their cheering words, by the hours they spent at my bedside, and by their conversation.” It also happens that the letters retrace the movement that has led from a subjective impression to an exercise of thought. Witness that meditation walk recounted by Seneca: “I found it necessary to give my body a shaking up, in order that the bile which had gathered in my throat, if that was the trouble, might be shaken out, or, if the very breath [in my lungs] had become, for some reason, too thick, that the jolting, which I have felt was a good thing for me, might make it thinner. So I insisted on being carried longer than usual, along an attractive beach, which bends between Cumae and Servilius Vatia’s country house, shut in by the sea on one side and the lake on the other, just like a narrow path. It was packed under foot, because of a recent storm .... As my habit is, I began to look about for something there that might be of service to me, when my eyes fell upon the villa which had once belonged to Vatia.” And Seneca tells Lucilius what formed his meditation on retirement—solitude and friendship.

2. The letter is also a way of presenting oneself to one’s correspondent in the unfolding of everyday life. To recount one’s day—not because of the importance of the events that may have marked it, but precisely even though there was nothing about it apart from its being like all the others, testifying in this way not to the importance of an activity but to the quality of a mode of being—forms part of the epistolary practice: Lucilius finds it natural to ask Seneca to “give [him] an account of each separate day, and of the whole day too.” And Seneca accepts this obligation all the more willingly as it commits him to living under the gaze of others without having anything to conceal: “I shall therefore do as you bid, and shall gladly inform you by letter what I am doing, and in what sequence. I shall keep watching myself continually, and—a most useful habit—shall review each day.” Indeed, Seneca evokes this specific day that has gone by, which is at the same time the most ordinary of all. Its value is owing to the very fact that nothing has happened which might have diverted him from the only thing that is important for him: to attend to himself. “Today has been unbroken; no one has filched the slightest part of it from me.” A little physical training, a bit of running with a pet slave, a bath in water that is barely lukewarm, a simple snack of bread, a very short nap. But the main part of the day—and this is what takes up the longest part of the letter—is devoted to meditating on the theme suggested by a Sophistic syllogism of Zeno’s, concerning drunkenness.

When the missive becomes an account of an ordinary day, a day to oneself, one sees that it relates closely to a practice that Seneca discreetly alludes to, moreover, at the beginning of Letter 83, where he evokes the especially useful habit of “reviewing one’s day”: this is the self-examination whose form he had described in a passage of the De Ira. This practice—familiar in different philosophical currents: Pythagorean, Epicurean, Stoic—seems to have been primarily a mental exercise tied to memorization: it was a question of both constituting oneself as an “inspector of oneself,” and hence of gauging the common faults, and of reactivating the rules of behavior that one must always bear in mind. Nothing indicates that this “review of the day” took the form of a written text. It seems therefore that it was in the epistolary relation—and, consequently, in order to place oneself under the other’s gaze—that the examination of conscience was formulated as a written account of oneself: an account of the everyday banality, an account of correct or incorrect actions, of the regimen observed, of the physical or mental exercises in which one engaged. One finds a notable example of this conjunction of epistolary practice with self-examination in a letter from Marcus Aurelius to Fronto. It was written during one of those stays in the country which were highly recommended as moments of detachment from public activities, as health treatments, and as occasions for attending to oneself. In this text, one finds the two combined themes of the peasant life—healthy because it was natural—and the life of leisure given over to conversation, reading, and meditation. At the same time, a whole set of meticulous notations on the body, health, physical sensations, regimen, and feelings shows the extreme vigilance of an attention that is intensely focused on oneself. “We are well. I slept somewhat late owing to my slight cold, which seems now to have subsided. So from five A.M. till nine I spent the time partly in reading some of Cato’s Agriculture and partly in writing not such wretched stuff, by heaven, as yesterday. Then, after paying my respects to my father, I relieved my throat, I will not say by gargling—though the word gargarisso is I believe, found in Novius and elsewhere—but by swallowing honey water as far as the gullet and ejecting it again. After easing my throat I went off to my father and attended him at a sacrifice. Then we went to luncheon. What do you think I ate? A wee bit of bread, though I saw others devouring beans, onions, and herrings full of roe. We then worked hard at grape-gathering, and had a good sweat, and were merry .... After six o’clock we came home.

“I did but little work and that to no purpose. Then I had a long chat with my little mother as she sat on the bed .... Whilst we were chattering in this way and disputing which of us two loved the one or other of you two the better, the gong sounded, an intimation that my father had gone to his bath. So we had supper after we had bathed in the oil-press room; I do not mean bathed in the oil-press room, but when we had bathed, had supper there, and we enjoyed hearing the yokels chaffing one another. After coming back, before I turn over and snore, I get my task done [meum penso explico] and give my dearest of masters an account of the day’s doings [diei rationem meo suavissimo magistro reddo] and if I could miss him more, I would not

grudge wasting away a little more.”

The last lines of the letter clearly show how it is linked to the practice of

self-examination: the day ends, just before sleep, with a kind of reading of the day that has passed; one rolls out the scroll on which the day’s activities are inscribed, and it is this imaginary book of memory that is reproduced the next day in the letter addressed to the one who is both teacher and friend. The letter to Fronto recopies, as it were, the examination carried out the evening before by reading the mental book of conscience.

It is clear that one is still very far from that book of spiritual combat to which Athanasius refers a few centuries later, in the Life of Saint Antony. But one can also measure the extent to which this procedure of self- narration in the daily run of life, with scrupulous attention to what occurs in the body and in the soul, is different from both Ciceronian correspondence and the practice of hupomnēmata, a collection of things read and heard, and a support for exercises of thought. In this case—that of the hupomnēmata— it was a matter of constituting oneself as a subject of rational action through the appropriation, the unification, and the subjectivation of a fragmentary and selected already-said; in the case of the monastic notation of spiritual experiences, it will be a matter of dislodging the most hidden impulses from the inner recesses of the soul, thus enabling oneself to break free of them. In the case of the epistolary account of oneself, it is a matter of bringing into congruence the gaze of the other and that gaze which one aims at oneself when one measures one’s everyday actions according to the rules of a technique of living.

2 years ago

Sound Structure as Social Structure by Steven Feld

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1lO9uk_ZsMOhbS6fVqPueJeu16pmcrvRd/view?usp=drive_link

2 years ago

The temporality of the landscape by Tim Ingold

https://drive.google.com/file/d/144IABF9GjQqb_28hsiHQAy9vitw8ou0c/view?usp=drive_link

2 years ago

The Agony of Eros Part 3 of 3

Here are the PDFs for each section in case you want to reference them

- https://msc-texts.s3.amazonaws.com/bch-taoe/5-fantasy.pdf

- https://msc-texts.s3.amazonaws.com/bch-taoe/6-the-politics-of-eros.pdf